The value of a single human being

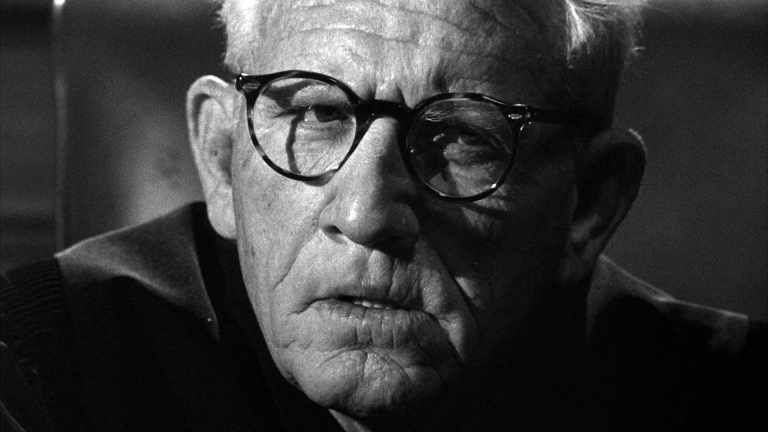

ALL IMAGES CREDITED TO MGM/UNITED ARTISTS/MOVIE LENS

How does an entire country full of people submit to a madman? How do millions upon millions of citizens allow their government to be co-opted by a murderous extremist, a man who strips basic rights from minorities, harms his own constituents and wages unprovoked war on the outside world? And if those people do allow it to happen, if they do allow such a man free reign over themselves and go along with it out of fear or complacency, are they culpable for that?

In the aftermath of World War II a series of trials were held by the Allies in the German city of Nuremberg. While Hitler and much of his inner circle had committed suicide once it became clear to them that the war was lost, there was a huge amount of Nazi officers, government officials and public servants who had assisted their leaders in the implementation of some of the 20th century’s most heinous crimes. A collection of these individuals were brought to trial by the Allies and prosecuted for their actions. One of these trials was conducted by an International Military Tribunal, composed of various Allied countries. This trial is the most famous, dealing with twenty-four top-ranking Nazi military officers and political officials but growing division amongst the Allies over how to proceed after that case was resolved lead to the dissolution of the Tribunal and the agreement that each Allied country would be free to hold additional trials in the zones of occupied Germany that they controlled. The American forces in Nuremberg conducted an additional twelve trials held before US military tribunals between late 1946 and early 1949. The third of these, held from March 5 to December 4, 1947, has become known as the “Judges’ Trial”. Sixteen German jurists, nine of them members of the Ministry of Justice, the others a mixture of judges and prosecutors, were tried for their involvement in implementing the Nazi regime’s infamous eugenics laws.

Directed by Stanley Kramer from a script by Abby Mann, adapting his original television play for the big screen, Judgment at Nuremberg is a fictionalised take on the Judges’ Trial. It essentially takes the idea and runs with it, inventing a collection of fictional participants through which to explore the idea of collective culpability. None of the defendants from the real trial are depicted here (sixteen is cut down to four); neither are any of the courtroom personnel. The purpose of the trial is much the same, however — American judge Dan Haywood (Spencer Tracy) presides along with two colleagues over the prosecution of four German judges for their involvement in enforcing “racial purity” laws, forced sterilisation procedures and generally allowing the rule of law to be superseded by the demands of the Third Reich.

This is a courtroom drama through and through; little attention is paid to the lives of the characters outside of the courtroom, save for a few sections in which Haywood tries to wrap his head around the thinking of the German citizenry during the war. Judgment at Nuremberg is laser focused on that one question, the question of culpability. This is a chamber drama, taking place largely in the one room as the prosecutor, Colonel Tad Lawson (a brimstone spitting Richard Widmark), lays out his case against the accused judges, while the defence counsel, Hans Rolfe, (an excellent Maximillian Schell; slick and difficult to get a read on) lays out the argument for his clients… perhaps innocence is the wrong word. The crux of Rolfe’s argument is that the four men he represents lack any legal accountability for their actions. They were judges, Rolfe argues, bound to enforce the laws of the land. The fact that the laws in question were so reprehensibly evil is not the issue.

This is the central question of Judgment at Nuremberg. Are we, as human beings, bound to a law greater than those of our country and if we are, how do the various systems and regulations society has put into place deal with those who break one set of laws and not the other? How do you assess the legal and moral culpability of four judges on trial for enforcing the law of their land? Is the legal culpability and the moral culpability even the same thing? And on a broader level, how do we survey the German people as a collective during World War II? Are they free of blame for the actions of their government? Hitler was elected to office after all. The Nazi Party did not become a dictatorial force overnight; it did so over a period of years, aided by the slow revocation of various civil liberties. Do the German people bear moral culpability for allowing that to happen? Did they have a moral duty to denounce the Third Reich later on when doing so would have certainly resulted in harm coming to themselves or their family? And how, if at all, does that moral culpability translate to a legal one?

To facilitate his case, Colonel Lawson introduces a number of witnesses including Irene Hoffman (Judy Garland; heartbreaking), a German woman at the centre of a tragic miscegenation case during Nazi rule, and Rudolph Peterson (a show-stopping Montgomery Clift) as a man forcibly sterilised by the courts on the grounds that he was mentally deficient. The most stomach-churning evidence though, is video footage of Jewish concentration camps taken by the British when they first began to liberate them. For this sequence, real footage is used, one of the very first times these kinds of images were made public to the world at large. Judgment at Nuremberg does not flinch in displaying this footage. As Lawson quietly narrates the footage for the courtroom, the audience is not spared the images — skeletal remains found in ovens, piles of naked bodies stacked high, rows of dead children. It’s one of the most horrifying scenes in all of cinema. Judgment at Nuremberg makes you bear witness to this. To truly understand the scope of the question at the heart of Abby Mann’s screenplay, these images are essential.

Mann’s screenplay is one of the film’s greatest assets, a methodical effort that moves carefully through the evidence as it builds up to it’s point. This is not, for lack of a better phrase, a simple damnation of the German people. Mann really wants to understand how the horror of the Third Reich could have happened. He desperately wants to figure out how such a malevolent force was ever allowed to come into being and in pursuit of that knowledge he offers the German people every excuse he can think of. This is, I should be clear, not in an attempt to absolve them of responsibility (the trial’s outcome and Judge Haywood’s moving final speech make it perfectly clear that Mann is unconvinced by these defences), but in an attempt to provide context. How did people justify these things? Mann’s script presents his conclusions and assesses these excuses as lacking.

Judgment at Nuremberg is a remarkably clear eyed study on the issue of culpability in the crimes of the Nazi regime. The group of judges on trial includes the truly repentant Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster); a man disgusted by his own complacency, and it is with this character that Abby Mann’s script finds it’s most informative subject. Janning is not a bad man; he respects justice, he respects the law. He does not hate and he is not a radical. But he still went along with it all. How does an essentially decent human being let such things happen without a fight? How does he carry out the laws of the Third Reich when he knows that the result will be the likely death of an innocent person? Judgment at Nuremberg doesn’t offer a satisfactory answer to this question because there isn’t one. There is no justification that excuses a man like Janning but there is equally no honest appraisal of him that defines him as evil. The conclusion that Judgement at Nuremberg arrives at puts the onus on us. The only way to prevent a phenomenon like the Nazis from reoccurring is to not allow the slightest lapse in justice or liberty, to stand up against oppressive regimes and dangerous people even when we ourselves are unaffected by the their actions.

Abby Mann’s script has some pointed observations about Western society. The West was all too happy to let Hitler do what he wanted to until he started to reach outside his own borders. And, the film is quick to point out, for all the condemnation of the Nazis’ forced sterilisation and racial purity laws, at the time of Judgment at Nuremberg‘s release interracial marriage was still illegal in some American states and forced sterilisation of the mentally impaired allowed in others, while Abby Mann was very aware of the phenomenon of McCarthyism, an example of institutionalised discrimination against those with specific political beliefs. Even in 2018 there are frightening echoes of the kind of slow erosion of civil liberty that Judgment at Nuremburg finds so dangerous. If the film has one message then, it is this: be very, very careful.